Rivers of Change

Dynamic Nature and Human Hubris

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays explore common topics from different perspectives and disciplines to uncover unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic explores human hubris against nature and how our attempts to exert mastery over our environments can often backfire. We’ll also explore the dynamism of change and how, by embracing it, we can improve our adaptability.

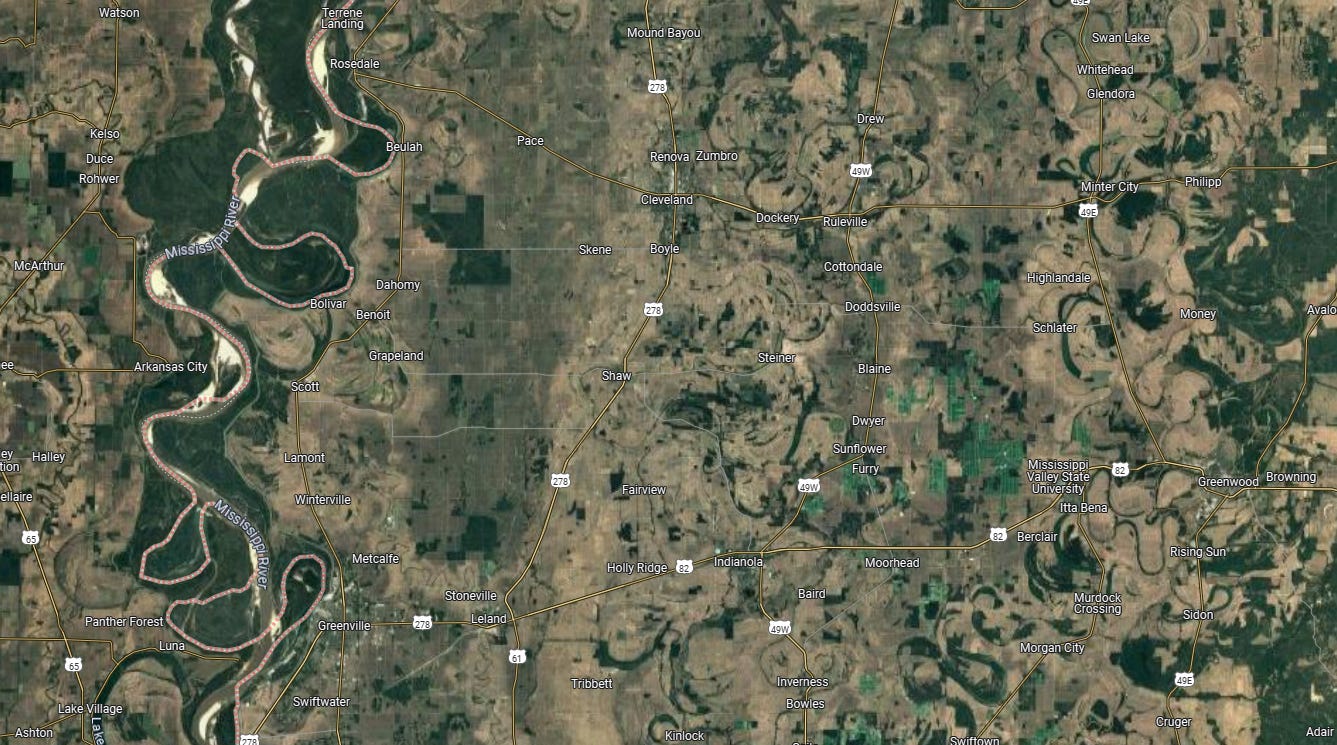

Recently, I was flying to the East Coast, and, while enjoying the view at 30,000 feet, I noticed fun loops and twists writhing across the landscape. I did a double-take when I realized these were the scars of the Mighty Mississippi, stretching 60 miles to the east of its current location. It’s a permanent testament to the volatility of that river in the past, a point Mark Twain and others talked about, that the Mississippi was never the same river year over year.

That was one hundred and fifty years ago, when the river was expected to flood and change. You didn’t do more than farm in the lowlands and, even then, you kept your buildings and equipment up on dry land. You built your towns on the bluffs and expected everything else to be at risk of loss.

But that’s annoying to have to deal with each year. You certainly can’t manage land rights well. Imagine buying property on the shore for your shipping business and, a year later, being a mile away from the river. Even state boundaries changed as the river fluctuated, shifting Kaskaskia, Illinois, from the east bank to the west bank, where it remains today. So, humans dammed, dyked, and directed the Mississippi to where it is now.

The benefit is that the river remains relatively unchanged from year to year.

The challenge is that the forces of nature are far greater than human hubris.

A fun fact is that the Mississippi is over 200 miles shorter today than it was originally. This began in 1929, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers literally cut off loops of the river, known as meanders, to reduce flooding and improve navigation. They also stopped natural change and locked the river in place.

The consequence, now, is that the annual expectation of flooding is transformed into a catastrophe, as the shorter, faster, and less dynamic Mississippi is expected to behave according to our wishes. The expectation is so high that we build massive amounts of infrastructure in the flood plains and then call it a ‘natural disaster’ when the flooding overwhelms these very unnatural barriers.

A case in point is the flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina. Another fun fact: Did you know that New Orleans has sunken below sea level over time? Not only did we build that city on a swamp, but we positioned it at the bottom of a river that now acts like a high-pressure fire hose, and then wonder why it flooded so badly.

In Tune With Nature

In contrast to the Mississippi, I proffer the Mekong River in Laos and Cambodia. These countries have embraced the natural flood cycles, built up on the bluffs, and accepted the ebb and flow as a fact of life. Their land use in the flood plain is communal, and property rights are managed differently.

And then there’s the Tonlé Sap. This natural marvel is a vast freshwater lake in central Cambodia, distinguished by its unique seasonal flood pulse. Each year, rains in the region flood the Mekong River and reverse the flow of water into the Tonlé Sap, filling the lake. Then, in the dry season, the channel’s flow flips back, and the lake steadily releases water into the lower Mekong delta.

It’s a natural pressure-release valve that absorbs the massive flood surge and slowly releases it, stabilizing the lower river basin. And when we talk about volume, the Tonlé Sap expands from roughly 2,500 square kilometers in the dry season to more than 12,000 square kilometers at its peak, and the water level in the lake rises nearly 30 feet! Put another way, that’s about 25 trillion gallons of water…

This dramatic change transforms the surrounding floodplain into a rich mosaic of floating forests and wetlands, supporting one of the world's most productive inland fisheries and providing crucial ecological balance to the lower Mekong system. Even better, humans have adapted to it, where entire communities exist on boats, and houses are on stilts.

Unnatural Expectations

It’s interesting to compare how much of what we consider natural disasters today are caused more by our own hubris than by nature. The Mississippi is one example, but Florida is just as bad: building on a literal sandbar, destroying mangrove forests, constructing million-dollar houses on barrier islands, and then acting as if hurricanes are unnatural.

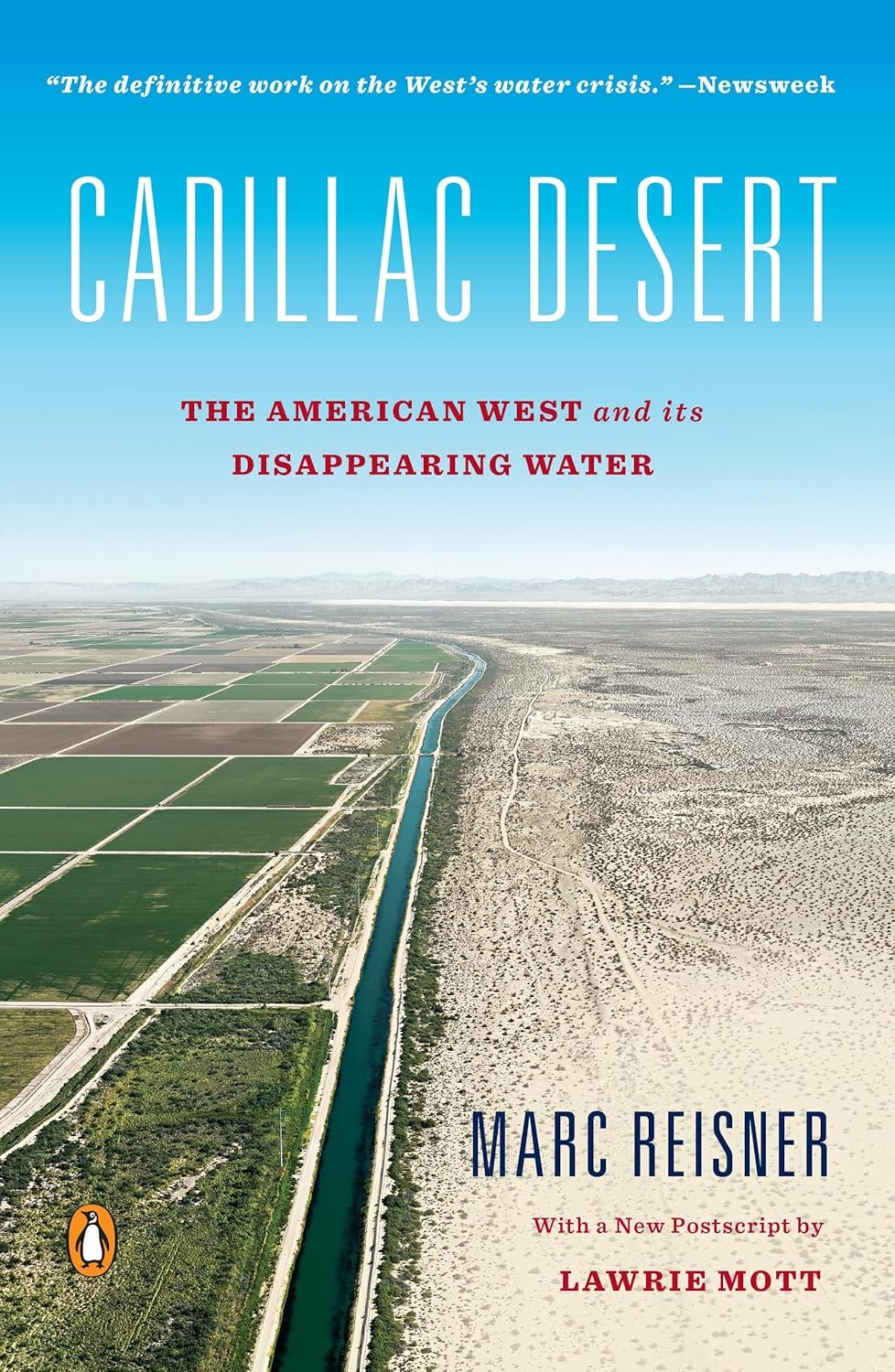

Similar water examples exist all across the US, from the extremely wet fact that the Tulare Lake basin in the San Joaquin Valley used to be an actual lake and, when they got a lot of rain, returned to being a lake in 2023, to how Arizona continues to build massive cities in the middle of the desert with limited concern for future water use. If you want a deeper primer into the fiasco of both issues, I highly recommend the book Cadillac Desert, which illustrates just how far our hubris goes.

But it’s not limited to just water. It’s actually so universal that it became a key lever to pull in the apocalypse at the end of my debut novel, Paradox:

Kira had marveled at how confident humans had been about where they built their cities. They built at the foot of volcanoes, next to huge fault lines, and along unstable waterfronts. The number of countries that had less than three hundred feet of elevation above sea level had surprised her. No wonder everyone was panicked about ocean levels rising. But that had nothing to do with the capability of Earth to handle the changes and all to do with the inability or reluctance of humans to adapt.

I think it’s fascinating to step back and look at what we’ve done as humans. It’s a marvel of both human ingenuity and engineering, as well as a marvel of hubris and historic and scientific illiteracy. I marvel because we are adaptable yet resist adaptation, where returning the Mississippi to a natural state is considered radical.

Yet we do the same thing mentally, where we dam and dyke our lives, demanding some artificial perfection and suggesting any deviation is a problem, or worse, a mental health issue. Instead, we need to work on allowing our knowledge to flow like those rivers of change and continue to expand, adapt, and flow, or, put another way, Learn, Unlearn, and Relearn like an aspiring polymath to avoid hubris in the future.

It’s embracing a mindset Bruce Lee shared:

Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.

When that model is embraced, it’s fun to change perspective to see how beautiful that chaos can be,1 as Richard Careaga pointed out by sharing this fantastic graphic of the changing river patterns created by Harold Fisk. I like to think of that as a map of my continued learning over time… at least, I aspire to that natural flow.

It’s the concept of learning, unlearning, and relearning that underpins what we attempt to do here. So, do you dam, dyke, and direct your thoughts in artificial ways, or do you release the flood of information to flow around and through you to uncover unique insights and solutions? Leave your thoughts in the comments.

If you’re curious to learn more about how these ideas impact our interpretation of climate change, I recommend The Climate is Changing, as well as where I address the Rates of Change conversation, because we aren’t seeing an abnormal climate, just like the Mississippi, and how so much of what we see isn’t natural.

Did you enjoy this post? If so, please hit the ❤️ button above or below. This will help more people discover Substacks like this one, which is great. Also, please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid member keeps these essays open for everyone. Hurry and grab 20% off an annual subscription. That’s $24 a year or $2 a month. It’s just 50¢ an essay and makes a big difference.

Further Reading from Authors I Appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

Goatfury Writes All-around great daily essays

Never Stop Learning Insightful Life Tips and Tricks

Cyborgs Writing Highly useful insights into using AI for writing

Educating AI Integrating AI into education

Socratic State of Mind Powerful insights into the philosophy of agency

I’ll point out here that chaos is traditionally a concept of the feminine. It’s the masculine that loves to dam and dyke and control. Part of the yin and the yang is embracing both the chaos and the order…

Nice essay. I took a boat from Siem Reap to Phnom Penh years ago and traveled through Tonle Sap, and seeing humans living amid the flux of that lake was incredible. Asia has a lot of that still going on, but the urge to control and gain efficiency is driving them away from living amid the flux. There are tradeoffs between control and change, but I like to think that flux is a solution to many problems, since excesses in one area fixes deficits in others. I often think about this in Texas, because of our twin maladies of floods and droughts, killing and destroying livelihoods. And yet rather simple earthworks can ameliorate both problems. But they do not go well with our style of development.

Tonle Sap is incredible, the economy arisen from tragedies epitomizes the culture there, From Laos to Cambodia side... Just spectacular feat of nature...