The Climate is Changing

Establishing a Baseline

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and investigate them from different perspectives and disciplines to come up with unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic looks at climate science in an effort to contextualize what we are seeing from climate change within the larger realm of what we should be expecting. I’m not trying to be absolute or prescriptive. I’m just trying to investigate a topic that I feel has a lot of questions we are ignoring. Therefore, this essay will attempt to investigate the baseline of where we are measuring the change in climate from, against the larger historic record. I hope I can open up questions and discussions because I think we have a chance to identify brilliant and overlooked opportunities to advance both humanity and all life on this planet.

Introduction

The climate is changing. Indisputable, irrefutable, undeniable. I’ve found, even those who are called climate change denialists, don’t actually deny that there is a change, they just disagree with the cause, rates, and especially the prescription of what to do about that change. I’ve personally been frustrated because having almost any discussion about the topic gets me accused of being anti-scientific and a denier, or questioned about my credentials to even discuss the topic where they use clear appeals to authority. Fundamentally, climate science has to be approached from a Polymathic mindset! It has to blend anthropology, geology, statistics, earth sciences, hydrology, fluid mechanics, biology, botany, and psychology just to name a few. Climate change is a classic wicked problem that requires counterintuitive investigation.

I’ll just be upfront; I don’t deny it and I won’t deny it and I use loads of climate science to discuss it. However, like our Quantum Superposition Problem and Politics, we’ve created a false binary that blinds both sides and therefore neuters any opportunity to affect real change. Today I’d like to break that binary and look at our climate baseline, why we have it, open the conversation to whether it is a valid baseline, and consider what impact these findings have on the recommended solutions.

Which Baseline?

The first major issue to address in discussing climate change is to understand which baseline we use to measure the change. It’s actually much less specific than you might think. There’s a general idea that its the temperature and CO2 levels somewhere right around the start of the industrial revolution. But what’s weird is that all the goals push CO2 and Temperature closer toward just prior to World War 2. I’d wager that’s because the beginning of the industrial revolution was also still the end of the Little Ice Age and a bit too cold but I can’t quantify that assumption, I just find it odd that it ends up being about 100 years ago. This also lands it about halfway through our quantified measurements of climate and, specifically, at a point where temperatures start to increase at a higher rate than was captured 100 years prior.

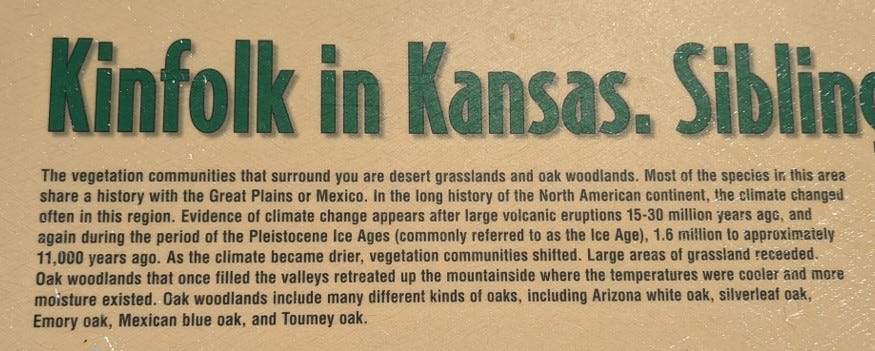

The second issue with this baseline is that it is fundamentally arbitrary because everywhere you look you find gems like this sign I found at Coronado National Forest that states: “the climate changed often in this region.” Further, not only did it change often, but it often changed cataclysmically from volcanic eruptions and other events, and the entire flora and fauna have dramatically changed over time.

While a first response might be that these changes appear to be over millions of years, we don’t have to go too far back to find out that temperatures were higher than today as Rosalind Rickaby from the University of Oxford captures:

Such evidence has shown, during the Eemian period, some 125,000 years ago, the U.K. (and the world) were very different places. It was much warmer: some 2° C higher than pre-industrial times (currently, it is up to 1.1° higher); ice sheets were much smaller; sea levels were some five meters higher; forests extended into the arctic circle and there were hippos in Britain.1

And, while yes, that was 125,000 years ago, we should mention that between then and now we had an ice age that ended only approximately 13,000 years ago. It’s especially worth noting that this ice age’s glaciers didn’t just gently melt, but catastrophically, likely through comet debris impacts known as the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis. This ending of the ice age resulted in some significant climate changes, notably the rise of ocean levels by over 400 feet as well as the subduction of the entire Indonesian shelf once the counterweight of the ice sheets was removed from North America. For context, think about the fact that zero of our current coral reefs existed 13,000 years ago. In fact, those sea beds were over 400 feet above the ocean and the entire water's salinity and pH completely changed with the influx of the ice sheets’ fresh water. Talk about dramatic climate change and animal adaptation!

We are currently not very far into an inter-glacial warm period and glaciers are continuing the recede. But even within this warming period, climate scientists have identified four cold and warm cycles during the past 2,000 years. These include the Roman Warm Period (c. 50 - c. 200), and the Dark Ages Cold Period (c. 400 - c. 800, the Medieval Warm Period (c. 800 - c. 1200), and the aforementioned Little Ice (c. 1300 - c. 1800). It cannot be denied that throughout the last 150,000 years, during a time when humans had achieved their extant form, we’ve seen temperatures both higher than and lower than today. This is evidenced in the recent receding of the glaciers which are uncovering human activity that existed before that glacier was there such as arrows and a Roman sandal being found in Norway.23 What this means is that the glaciers have expanded and contracted and have, today, merely receded to levels known to Vikings 1000 years ago during the Medieval Warm Period.

Not only is climate dynamic, with micro and macro trends, but another challenge also emerges that we must balance two, somewhat competing, analysis concepts. That of gradual incrementalism which permeates geology and climate sciences, with that of dramatic and often catastrophic change such as the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis. Incrementalist scientists raise the red flag of the rate of climate change today yet, we need to accept a combination of intermittent dramatic change, and subsequent re-stabilization that is evident in the historic precedent. In doing so we must start looking at a much larger system of systems analysis to see whether it is out of the norm.

Establishing a proper baseline for temperature is also confounded by the fact that optimal temperatures for global flora and fauna are warmer than where we are today. Again, it doesn’t take much to compare the last Ice Age against the fossil record of the Jurassic period to see that warmer temperatures are correlated towards improved biomass of plant and animal life, ie, more, and bigger. This also affects humans where a recent Lancet study identified that rising temps are saving 166,000 lives per year.4 While we may not know the total impact of warming, we do know that cold has catastrophic consequences on human, animal, and plant life overall.

Further, the baseline isn’t only about temperature. We are told that we must also stop the increase in CO2 due to its role as a greenhouse gas. Yet, we run into the same problem that CO2 levels have also been dramatically higher in the past. For instance, plant life is optimized for about 1200 ppm of CO2 for photosynthesis. For context, we are currently at 415.26 ppm of atmospheric CO2 and therefore, greenhouses growing plants are adding supplemental CO25 to foster better plant growth where:

For the majority of greenhouse crops, net photosynthesis increases as CO2 levels increase from 340–1,000 ppm (parts per million). Most crops show that for any given level of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), increasing the CO2 level to 1,000 ppm will increase the photosynthesis by about 50% over ambient CO2 levels.6

We have to consider that over the course of evolutionary history, nothing optimizes for an environment that does not reflect the average across time. Therefore, we can accurately deduce that, for the extent of plant life on planet earth, it experienced 1200ppm of CO2 for the majority of that time. And that isn’t the maximum, as during the Devonian, and again in the Triassic period, CO2 levels were over 2000ppm.7

This gives us another counter-intuitive insight in that CO2 is a fertilizer for plants, not a pollutant. In fact, the current increase of CO2 over the past decades has led, according to NASA to the marked greening across the world, including deserts!89

Which baseline to select must recognize that the climate has always been changing in both temperature and CO2 levels where, even within our own species’ history, we have seen both higher and lower levels of both. So why have we chosen the baseline we have?

Why this Baseline?

One of the first reasons is that we don’t really have very much history in measuring temperature and CO2 specifically. We are just learning and have yet to fully contextualize the full climate history to better understand. We look at the numbers from the late 1700s and see a rise and then a more dramatic increase in the last 100 years and extrapolate worst-case scenarios. Yet this very short period of measurement doesn’t capture the entire system as we’ve noted above. This measurement and availability bias drives inaccurate assessment of future risk as captured in the book How Risky Is It, Really: Why Our Fears Don't Always Match the Facts.

Another reason for selecting this baseline is that it also represents the timeframe in which our current geopolitical boundaries have, largely, been established. So instead of having bands of mobile humans who can migrate, we have a fear that the countries of Denmark (average 111ft above sea level), the Maldives (average 4ft above sea level), or the State of Florida (average 100ft above) will disappear under water. Since this would effectively eliminate these entire regions, where would these people go? But this isn’t a problem with the climate, this is a problem of artificial geopolitical boundaries, especially if the climate baseline is suboptimal for most life on earth.

Lastly, selecting this particular baseline doesn’t make sense until you consider that it might not be completely logical. The more I look at the established baseline the more I find it suspect because it falls into what’s called a nostalgia bias or a rosy retrospective where things in the past are always valued more than the future. This nostalgia bias, then coupled with the status quo bias, puts us in a double bind. Let’s not forget we have to add on negativity bias where we put much more effort to avoid a perceived negative outcome than we do to achieve a positive outcome. This leads to a multi-factor situation where humans are resistant to any change, and when that change is inevitable, negativity bias colors it as worse than it is.

The Negative Impact of Selecting the Baseline

From a scientific analysis perspective, selecting this baseline establishes a bias of correctness. It begins the quantum superposition problem by creating a binary that this baseline is correct, and therefore good, and deviations from this baseline are bad. It biases the conversation so that if you begin to question the solutions, you are cast as a ‘science denier’ or otherwise. You begin to see appeals to authority where claims of “scientific consensus” and that “97% of scientists agree” begin to shut down the conversation. (But even this isn’t true because of a sampling bias where 97% of scientists who write about the preferred baseline agree, not 97% of all scientists in the field)10

One of the biggest challenges with climate science is in ensuring contextualization and not jumping too far too fast. For example, prior to the Apollo missions, models of the moon only depicted one side because literally, no one had seen the other side of the moon. Therefore, the other side of the moon was blank until recently. But unlike the model of the moon, where we were OK with a blank spot, current discussions of climate change don’t tolerate the identification of blanks or even questioning the baseline. In a complete irony to the incrementalism of climate science that leads us to the fear that the rate of change is too dramatic; the proposed responses are rejecting incrementalism for “bold changes”11 with just as ignorant an understanding of the systems of systems impact.

This baseline immediately puts us in a very specific paradigm and this paradigm has begun to take on aspects of religious fervor, as we covered in a previous essay on Religion as a Psychology In this case, the climate alarmism paradigm has established the temperature change as the apocalypse, the sin as CO2, and the repentance as an extreme reaction. This reaction manifests in the assumption that we can, or should, not only Stop climate change12 but reverse it back to previous levels. You can see this in dramatic solutions like vacuuming carbon dioxide from the air,13 using aerosols to reflect the sunlight and cool the planet,14 or even reducing the population to tackle the problem.15 There is no shortage on the number of articles, studies, essays, and commentary where the goal is to stop and even reverse the warming trends with solutions that, under even a cursory investigation, look much worse than the problem.

The World Wildlife Federation even went so far as to suggest that we “stop climate change before it changes you!” This is honestly an odd tact when you tease it apart because it’s basically saying, stop evolution before you evolve. It’s completely unscientific and seems to assume that humans are somehow not natural. Underpinning this statement is the refusal to allow humans, or anything else, to adapt. It’s equal parts ignorance and hubris wrapped in religious psychology. Ignorance of history, and hubris to think we can freeze billions of years of evolution.

Much of this reaction is due to the fact that any major climate change actually does require the adaptation of humans. 13,000 years ago, Indonesia was a much larger landmass and half of North America was under one mile of ice. Today whatever civilizations were in Indonesia are underwater. In fact, with a nearly 400-foot rise in ocean levels, considering the UN currently estimates 40% of the population lives on the coastlines, (which was likely a much higher percentage 13,000 years ago), almost all of the human population at that time would have had to relocate to higher ground.16 But back then, without the nation-state structures, it was just a human migration. And in case you are curious as to whether this actually occurred, consider that every human group has a worldwide flood mythology.

Missing The Positive Potential of Climate Change

Grasping onto the established baseline and having the hubris to believe we can stop the change causes us to ignore ways to adapt to the change. It also ignores what sorts of major benefits could be achieved if we did adapt to the change, not only for humans but also for the planet.

Imagine for example, if we resolved ourselves that New York City was going to be submerged, what sort of effort could we conduct to address that? Maybe the solution is to relocate New York City to higher ground. The opportunity emerges to throw away city designs according to principles and structures established 400 years ago. Instead, we could re-imagine the entire city.

Perhaps we use the Boring Company to locate all of the utility and transportation infrastructures underground. We could then integrate greenspaces into the cityscape and avoid the concrete jungles which drive increased anxiety and depression in humans17 and are also better for plant and animal life. We could develop better refuse and recycling programs that further reduce pollution. Power systems could be better designed, and industrial zones could be better sequestered.

Yet these ideas are overlooked and ignored because we believe we can, and should, stop climate change, and we don’t focus our time, money, and talent on these ideas. Certainly, it will cost a lot of money, but that proactive investment today is pennies on the dollar compared to a reactive adaptation. It also will take an incredible paradigm shift of national sovereignty when considering what to do with national populations that would have to migrate. Yet in looking at history, what is it but the constant flux of populations and geo-political boundaries? Why should we freeze everything at some arbitrary snapshot of the early 20th Century when so much positive opportunity exists to adapt and evolve?

Conclusion

I think it takes some humility to step back and contextualize this problem. It certainly isn’t a safe place to dabble as you are addressing a lot more psychological problems of biases and religious behavior than you are actual climate science and people don’t care to have their beliefs questioned. It also takes a lot to tease apart the assumptions of why we’ve selected the baseline and to be able to address the methods by which we are measuring impact or even rates of change! Further complicating this situation are the geopolitical challenges that are woven through the entire discussion!

The negative impacts of climate change aren’t even, as we’ve discovered, about the planet per se, but about economics and geopolitics. I just ask, can we get past nationalistic and somewhat arbitrary boundaries for the betterment of all life on earth? Or, should we spray questionable aerosols into the atmosphere, which could likely dramatically backfire, to maintain the status quo on a dynamically changing planet?

My stance is that we should focus on adaptation, not the status quo. I don’t know what the right answer is, but I do know that much of the existing climate change paradigm is myopic, often wrong, and rarely asks the right questions. This causes us to potentially miss the most brilliant opportunities to advance both humanity, and all life on this planet.

Here’s a deeper analysis on the rates of climate change throughout history:

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

University of Bristol. (2022, July 7). Hippos roamed when temperatures were higher. Phys.org. https://phys.org/news/2022-07-hippos-roamed-temperatures-higher.html

Duncombe, J. (2021, September 16). Stunningly well-preserved arrows with feathers revealed by melting ice sheets in Norway. IFLScience. https://www.iflscience.com/editors-blog/stunningly-wellpreserved-arrows-with-feathers-revealed-by-melting-ice-sheets-in-norway/

Berglund, N. (2022, August 15). Why was this flimsy Roman-looking sandal buried beneath the snow in an ancient dangerous Norwegian mountain pass? Science Norway. https://sciencenorway.no/archaeology-history-iron-age/why-was-this-flimsy-roman-looking-sandal-buried-beneath-the-snow-in-an-ancient-dangerous-norwegian-mountain-pass/2008637

Watts, N., Amann, M., Arnell, N., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Beagley, J., Belesova, K., … Costello, A. (2021). The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Code red for a healthy future. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(7), e386–e401. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00081-4

Oklahoma State University Extension. (n.d.). Greenhouse carbon dioxide supplementation. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/greenhouse-carbon-dioxide-supplementation.html

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. (2000, September). Carbon dioxide enrichment in greenhouses (Fact Sheet 00-077). http://omafra.gov.on.ca/english/crops/facts/00-077.htm

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_dioxide_in_Earth%27s_atmosphere

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. (2016, April 26). Carbon dioxide fertilization greening Earth. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2016/carbon-dioxide-fertilization-greening-earth

Viegas, J. (2013, July 8). Carbon dioxide linked to desert greening. Sci.News. https://www.sci.news/othersciences/geophysics/science-carbon-dioxide-desert-greening-01209.html

Tuttle, I. (2015, October 19). Climate change: No, it’s not 97 percent consensus. National Review. https://www.nationalreview.com/2015/10/climate-change-no-its-not-97-percent-consensus-ian-tuttle/

Michaels, D. (2020, August 12). Climate change incrementalism is no longer a viable option. Medium. https://medium.com/swlh/climate-change-incrementalism-is-no-longer-a-viable-option-34bb9b0a2d82

Natural Resources Defense Council. (n.d.). How you can stop global warming. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/how-you-can-stop-global-warming

Huang, P. (2022, May 2). Scientists are trying to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/05/02/1095097566/carbon-dioxide-removal-climate-emissions

Meredith, S. (2022, October 13). What is solar geoengineering? Risks and benefits of sunlight reflection. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/10/13/what-is-solar-geoengineering-sunlight-reflection-risks-and-benefits.html

Le Page, M. (2022, November 16). Tackling population growth is key to fighting climate change. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg25634124-600-tackling-population-growth-is-key-to-fighting-climate-change/

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (n.d.). Population in coastal areas. https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/natlinfo/indicators/methodology_sheets/oceans_seas_coasts/pop_coastal_areas.pdf

Derbyshire, D. (2011, July 20). A rural life is better: Living in a concrete jungle really is stressful and can make you vulnerable to depression. Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2006988/A-rural-life-better-Living-concrete-jungle-really-stressful-make-vulnerable-depression.html

Here's a new gem to consider when northern Greenland was 60F warmer and a temperate forest just 2 million years ago. They mention plant and animal life flourishing.

https://gizmodo.com/oldest-dna-2-million-years-greenland-ecosystem-1849860675

Very stimulating article! I finally read it once and will need to read it again. Now that I'm getting a bit used to your arguments, they don't sound as "nutty" as they did initially!

If that's OK with you I'd like to create a few comment threads to discuss different parts of your article.

Most of the discussions around climate change policy are very binary -- net zero or not. That's the same with most policy discussions. More taxes or less taxes? More immigration or less immigration? Binary choices are easy to make -- I can simply look at what most people in my party think and make the same choice. I can even just flip a coin! It's a bit like multiple choice tests in school. You don't even have to understand anything in the class and yet you can get 1/4 or 1/5 of the answers right.

What you are proposing is much more difficult (but ultimately potentially more satisfying). First I need to have a finer grained understanding of what the IPCC actually says. "OMG we're all going to die of climate change" doesn't cut it. What exactly am I afraid of? What is the probability that will happen? How confident am I? Basically I pretty much have to read the AR6 WGI report (which is 3,000-page long). Already the summary for policymakers introduces biases and errors.

Then I need to understand what are my own assumptions, beliefs and biases. For instance when you write that people have always migrated, my first reaction was "But there will be war! Countries will defend their borders! And now that we have nuclear weapons such wars will be horrible!" That's a gut feeling. That's my "think fast" system speaking. I now have to look at those beliefs coldly. I also need to find more of my beliefs.

Finally, you're inviting us to *imagine* different futures. That's the hardest part. It's so easy to think about a finite "policy universe" (net zero or not). It's much more demanding to start saying "OK, if CO2 reaches 1,500 ppm, what then?" Well, oceans will rise by Y meters and so on. "OK, what will people do? What will this look like?" You show this kind of imagination when you present an alternate New York City.

I'm looking forward to continuing the discussion. I appreciate your humility. You wrote "I don’t know what the right answer is." Few (no one?) amongst people who write and talk the most on climate change say "I don't know." They seem so sure (e.g. The Unhabitable Earth), but they never explain, let alone question, their assumptions and beliefs. Thank you for doing that and motivating me to do the same!