Stare Into Evil

The Thin Veneer of Civilization

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays explore common topics from different perspectives and disciplines to uncover unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic builds on the idea of Inversion, focuses specifically on evil, and stares directly at it. In doing so, we can improve our understanding of history, cultures, and our current civilization to appreciate how thin the veneer really is.

Intro

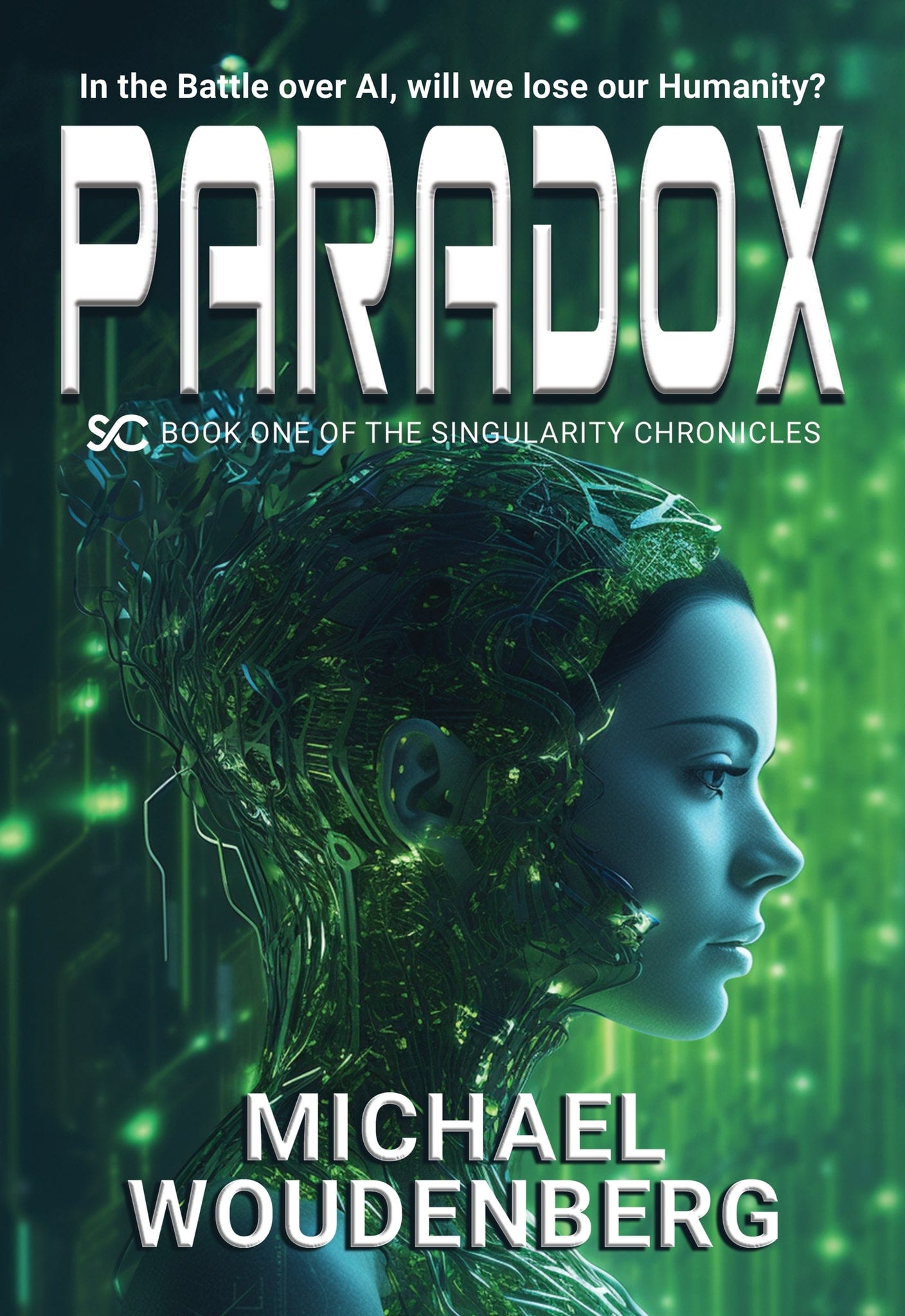

Recently, we explored the power of Inversion and how that often involves focusing on the negatives in order to identify more positive outcomes. We looked at Threatcasting as a technique, and it’s a tool I used in my own Science Fiction writing. In my debut novel, Paradox, I found the fastest way to kill humans was to give them the excuse to do it themselves. As I plotted the demise, I had to stare into the face of how thin the veneer of civilization really is:

There’d been so much good done for humanity. Innovation, equality, healthcare, flourishing! The chaos hadn’t started until Prometheus had released Excalibur. Even then, Mother was helping by exposing the false information and trying to provide the truth.

But humans didn’t want the truth. There was something perverse about how thin civilization truly was and when it was breached, humans turned and attacked humans. It hadn’t helped that so many social structures that created the stability that allowed civilization had been attacked and torn down years before Mother. Structures did constrain, but when the structure supported something bigger and you ripped them out, that larger benefit couldn’t support itself under stress or fracture. When Excalibur cracked the thin veneer that remained, it just crumpled back to unstructured chaos.

Now, this is, in theory, Science Fiction. I joke that I hope no one uses Paradox as a guidebook because that would be too easy. It’s too on point to human psychology, but that same knowledge can be used for good or evil. However, to understand good, you have to perform an Inversion and stare evil directly in the eyes. Let’s see how deeply we really need to look to better understand the world we live in.

Staring Into Evil

Jared Bruder, and I were recently talking about what would happen if our food supply got seriously disrupted. We live in Tucson, Arizona, and it’s a desert. In my neck of the woods, saguaros, there are people with gardens, small animals, and quite a few horses. The same up near where Jared lives. Further out, you find some smaller cattle ranches and a smattering of food farmers. Yet for most people in the 1+ Million town, it’s the grocery store or nothing.

So what happens if the food runs out?

Thankfully, the average American can go about 75 days without food before reaching a healthy body fat percentage, but… I can tell you they’re not waiting that long before doing something. So what’s really going to happen?

Well, Tucson has a decent presence of cross-border gangs. These folks wouldn’t hesitate to take over gas stations and go on a lockdown of resources around town. When the cops are just as hungry, they are likely to side with food providers over starving law and order.

OK, so I live out of town, so what? Well, that works for a bit. My 1400 SF garden can provide… but it doesn’t do more than give the family a hobby and a little fresh supplementation. I have fruit trees… that produce just once a year and are still young.

If the food supply has that sort of issue, we also have to assume that the power is out as well. Or at least intermittent. So, now add all that to the high probability of roving gangs looking for food. Then consider that gangs, of any ethnicity, willing to rob a family of food in the desert, guarenteeing death, would also have limited hestitation to murder and rape. The best hope is working together with your neighbors and creating a stronger gang, or at least a strong enough gang to hold off the intruders.

So what would you do? What would you trade for survival?

Confronting History

Let’s be honest. Outside of the WWII generation, which grew up in the Great Depression AND fought in a war, no one since then has any idea what survival really entails. Even the Depression, when some families were forced to sell their children, isn’t at the level of evil I’m talking about yet.

Let’s go a few levels deeper and visit an experience in the same time frame but on the other side of the world. I’m referring to the Holodomor Famine that killed 4 million Ukrainians. That death toll doesn’t even convey the depth these people suffered. Take, for instance, Timothy Snyder writing in Bloodlands, that at least 2,505 people were convicted of cannibalism between 1932 and 1933 in the Ukraine.

But it gets worse. According to one witness:

“I saw villages that not only had no people, but not even any dogs and cats. and I remember one particular incident: we came to one village, and I don’t think I will ever forget this. I will always see this picture before me. We opened the door of this miserable hut and there… the man was lying. The mother and child already lay dead, and the father had taken the piece of meat from between the legs of his son and had died just like that.”1

And yet, there’s just one more level. That man might be forgiven for survival, but there were Ukrainians who sold human meat. This isn’t an attack on Ukrainians because there are levels we’ll all go for survival like this. Hell, these people weren’t killing people, just selling dead bodies to feed others. Now think of those gangs who’d just kill you for your food or your women. So, what would you do to avoid that?

What Would You Do?

Let’s pull back because its pretty damn dark to consider that just 100 years ago, this is what people in the US and overseas were facing for survival. So, with that comparison, what would you accept to avoid these outcomes?

This question isn’t just mere speculation, I want to contextualize some of the things that we find highly problematic today, things like:

Engaging your daughter to a cattle rancher to increase your blood relations

Turn in your friend for ‘wrongthink’ in order to get food

Trading sex for survival

Killing someone who is a threat

Marrying an older man, not for love, but for safety

Pretending your wife is not your wife to avoid being killed

Now, if that last one strikes you as interesting, it happened three times in the Bible. Abraham did this twice. Once in Egypt (Gen. 12:11-13) and once in Gerar. (Gen. 20:2) Isaac did the same thing later with Rebekah (Gen. 26:6-7). As for the rest of those examples, well, they’re the stories that make up our myths, fables, and histories.

While we view these things as abhorrent today, it helps to consider that those decisions weren’t made today. They were made in a time and place when these may have been the best option for survival and, quite possibly, even thriving in those circumstances, as regressive as that seems now.

Case in point, if you were revolted by the idea of cannibalism, a long-standing tradition called the “Custom of the Sea” had sophisticated protocols for cannibalism. In essence, if a crew were stranded without hope of rescue or provisions, the traditional rule was: first, eat any bodies of those already dead; if none were available, draw lots fairly to choose someone to be killed for the others to consume.

As historian A. W. Brian Simpson documented:

If properly conducted, cannibalism was legitimated by a custom of the sea; and the popular literature, augmented by the unrecorded tales seamen told each other, ensured that there was general understanding of what had to be done on these occasions and that survivors who had followed the custom could have a certain professional pride in a job well done; there was nothing to hide.

The novel Moby Dick is inspired from the story of the US Whaling ship Essex, shipwrecked by a sperm whale, and whose survivors followed this custom, theirs tailored because of the much closer kin relationships the sailors shared.

Again, this shocks modern sensibilities because situations like this are just not asked of us. To best understand these situations, a great tool is called Exegesis. It’s a theological term that means: “consider[ing] the original context with the culture, language, intentions, and even biases of the original authors and audience in mind.” A great example is the Commandments in the Old Testament of the Bible, known as the Torah. Today, the idea of bond-servants, restitution for rape, stoning, etc. sound barbaric and evil. However, if we look at how much thinner the veneer of civilization was back then, we discover that the Torah was one of the more progressive bodies of laws that existed at that time.

So, back to what you would do?

As has become a trope here on Polymathic Being, the first step is to understand and acknowledge that what you’d do in the circumstances you enjoy today is not anywhere close to what you’d do if that veneer of civilization collapsed. The actions you find abhorrent today might be acceptable then and not only permissible, but the best option.

Summary

Our civilization and the structures that hold it up are a thin veneer on a natural world that’s not utopic. When you consider the existence of our nearest great-ape cousins, our human ancestors just 150 years ago, and what happens, even today, when that veneer cracks, it adds perspective.

This leads us to two major thoughts I want to weave together.

When reviewing history, it’s essential to understand what they were facing.

When reviewing the future, it’s important to stare into the eyes of evil and ground your ideology in the reality of what you might do.

With these two in mind, we are better prepared to recognize the structures, cultures, and social mores that hold our civilization together. As Chesterton’s fence directs: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

Staring into evil is a powerful tool, an Inversion, to understand history and yourself. If you haven’t, or won’t, you’ll never fully recognize how thin that veneer of civilization is and you’ll be more fragile when that civilization is threatened. That fragility is what I exploited in Paradox, where the fastest way to kill billions was to give humans the excuse to do it themselves. Staring into evil is a good way to prepare yourself, so you can help prevent chaos by protecting the systems that keep evil at bay.

So, what would I do if our food supply got seriously disrupted? Well, I’m not giving away all my plans, but I will surround myself with friends, better understand traditions and social structures, combine resources, and anticipate the worst. As Sam Alaimo explains this concept in “Why We Should Train for the Worst Case Scenario,” which I use to look around right now and do what I can so that we never have to see how thin that veneer of civilization really is.

As crucially, it helps provide perspective for how good we really have it. As Kyle Shepard wrote in a recent note: “How can anyone realize how good they have it without experience or understanding how bad things can be?” I hope what we stared at today helps us understand how bad it can be, so that we can be prepared to face that while also appreciating how good we really have it today and have gratitude.

“Tradition is a set of solutions for which we have forgotten the problems. Throw away the solution and you get the problem back.” — Donald Kingsbury

Did you enjoy this post? If so, please hit the ❤️ button above or below. This will help more people discover Substacks like this one, which is great. Also, please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid member keeps these essays open for everyone. Hurry and grab 20% off an annual subscription. That’s $24 a year or $2 a month. It’s just 50¢ an essay and makes a big difference.

Further Reading from Authors I Appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

Goatfury Writes All-around great daily essays

Never Stop Learning Insightful Life Tips and Tricks

Cyborgs Writing Highly useful insights into using AI for writing

Educating AI Integrating AI into education

Socratic State of Mind Powerful insights into the philosophy of agency

Ukrainian Famine of 1932 and 1933. Hearing before the Committee on Foreign Relations of the United States Senate, August 1, 1984.

This was kind of dark.

Maybe you know about these ideas, maybe not. Living in Utah I learned from LDS about the idea of the “two year store”. I wrote about that once:

https://collettegreystone.substack.com/p/thoughts-on-being-civil-and-self

Other sources: https://easyhealthyfoods.com/why-do-mormons-store-food/

The LDS church used to provide canneries (25 years ago) where anyone could go and can their own food, now there are only few actual canneries: https://ezprepping.com/lds-cannery-food-storage-center-locations-near-you/#canning-locations

There’s a whole network of preppers: https://prepper.com/

You don’t have to rely on the grocery store - ever - if you don’t want to.

I know that wasn’t the gist of what you were presenting here….

civilization exists because humans have found that it works better than marauding.

in the short term and under stress, people can do the unthinkable.

there may be more resiliency in relationships than you imagine. T. Jefferson said,

"you don't know how much is enough, until you have had too much"

and I might add, until you have had too little.

our self-image, our morality, our goodness depends on religion, or how we define what is sacred.