Raise Your Child Like Your Dog

The Failure of Gentle Parenting

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays explore common topics from different perspectives and disciplines to uncover unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic addresses a critical failure in how we raise our children through the well-intended but misapplied philosophy of Gentle Parenting. We’ll see how this concept fails and how we’d be better to raise our children like we raise our dogs. These methods teach temperance, patience, and focus that mature their agency.

Intro

The other day, while on a cross-country flight, I encountered an increasingly common altercation. It’s the type you see everywhere anymore, the one where a mother is begging a child to behave, never raising her voice, never daring to issue a command or edict, and trying to negotiate with promises of treats, toys, and more. As often happens, the child knows they have the upper hand. Mom has ceded her authority under the auspices of kindness, not realizing the result is one of the meanest things you can do to a child.

The irony is that we know this doesn’t work, and the best example I can provide is how well we understand this with our fur ‘children’ and why we should raise our kids like we raise our dogs.

Raising Our Dogs

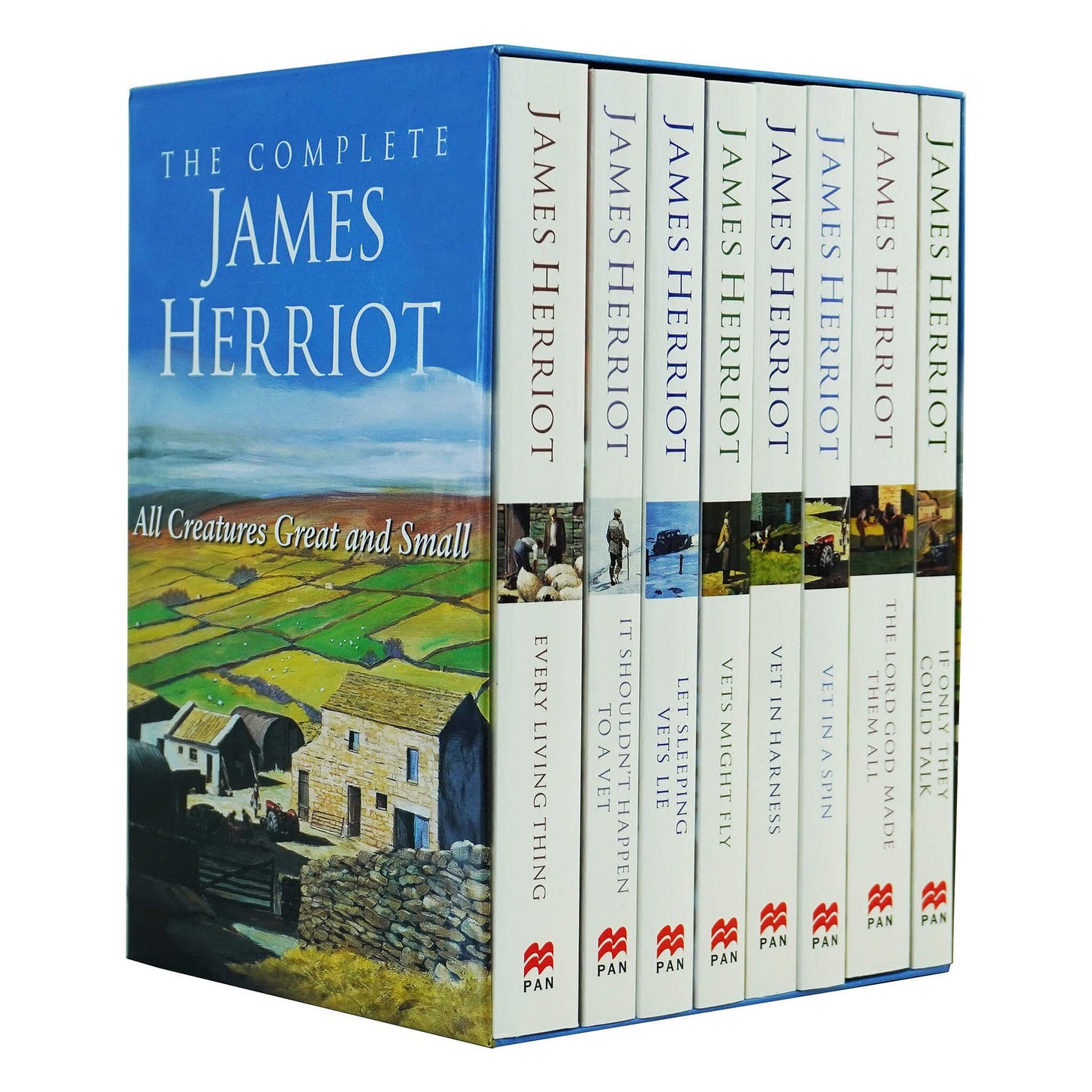

James Herriot, one of my favorite childhood authors, was a veterinarian in England and wrote a fantastic series starting with All Creatures Great and Small. In one of his stories, he relates the tale of Ruffles and Muffles, two West Highland White terriers belonging to Mr and Mrs Whithorn. These were nasty dogs; vicious, ill-tempered, and mean. At first, he wondered whether they were just from a poor breeder, but after these two dogs died and were replaced with two more, with identical names, it became clear that the problem wasn’t the dogs; it was the owners. Mr and Mrs Whithorn did nothing to train their dogs. They doted on them, spoiled them, and had two of the most obnoxious dogs in Harriot’s vast experience.

In a related story, Herriot described Tricki Woo, a pampered Pekingese so spoiled by indulgent care that he became overweight, unhealthy, and lacking boundaries. He stepped in, took the dog away, imposed a strict diet and regular activity involving rough and tumble play with his own pack of dogs. Tricki Woo transformed into a healthy, responsive companion, at least until she got back to her owner.

Multiple studies have shown that with dogs, an authoritative style relates to significantly better outcomes for the pets. One study found: “Authoritative owners (high warmth + high expectations) produced the most secure, persistent, and socially responsive dogs.”1

In raising the two dogs we’ve had, we’ve followed the authoritative approach. Our first was a Labrador named Nilla, and, anticipating her future ninety-pound size, we set firm expectations and trained her extensively. We’d constantly get comments on how well-behaved and pleasant she was compared to other labs (think Marley and Me). For example, while our pup was in the park, playing with kids daily, these same kids’ dogs were locked up at home, untrustworthy in that environment.2

We now have a beagle named Peanut, and started with a similar approach, but realized beagles are not labs.3 We’ve had to adjust our tactics and have found a balancing point where we are still authoritative, but our expectations are a bit lower. Beagles are sassy, sweet, and stubborn as hell, and it took some adjustments, but Peanut needs a lot more ‘No’ commands than Nilla ever did.

It’s pretty clear how authoritative training with dogs works and how permissive training leads to poor behaviors in our canine friends. The bigger problem is that permissive training also doesn’t work with our children. We should really be raising our children the way we know we should be raising our dogs.

Raising Our Children

Now, I should clarify, when we describe authoritative, we aren’t talking authoritarian. For a baseline, let’s look at how Abigail Shrier differentiates the two in Bad Therapy:

The “authoritarian parent” values a child’s obedience as a virtue, holds a child’s behavior to an absolute standard, works to keep the child in his place, restricts his autonomy, and does not ever encourage a give-and-take discussion about her rules.

The “authoritative parent,” however, is loving and rule based, She attempts to direct the child’s activities in a rational manner, encourages a give-and-take with her child, but “exerts firm control at points of parent-child divergence” Where her point of view on a householde rule ultimately conflicts with that of her child, she wins. She maintains high standards for her child’s behavior “and does not base her decisions on group consensus or the individual child’s desires.”4

What we see with Gentle Parenting is neither of these. It’s also worse than these. Simply put, the gentle parent is akin to the Devouring Mother,5 where the child’s autonomy is stifled, but by indulgence rather than intrusive control. This is because permissiveness deprives the child of the frustration needed for growth, a topic we explored in You Can Do Hard Things. Gentle parents are high warmth coupled with low expectation and permissive, leading to children with impulsivity, narcissism6, poor self-regulation, domineering behavior, and aimlessness.7

Some argue that Gentle Parenting is nested under Authoritative,8 and that it merely adds Gentle. However, this is an argument of semantics and intention, not application, as evidenced by the multitude of gentle parents who lack any authority over their children. Healthy, Authoritative parents aren’t mean; they have standards and high expectations, and Gentle Parents have fallen into the permissive.

Another point to clarify is that Helicopter parents, like so many of Gen Z, are closely related to the gentle parenting Millennials embraced; they’re both on the permissive side of the scale. These parents have the same goals, but devoured their children’s agency with over-intervention. Gentle parents inherited many of the pathologies of helicopter parents and just took the next step.

This occurs because the world is chaotic, and gentle parents don’t want to be seen as tyrannical. Consequently, in a classic over-index, they avoid imposing constraints to mitigate that chaos and then expect the child to navigate in a healthy manner. However, that child can’t even regulate themselves well yet. They need structure, just like a puppy needs structure, so they can build confidence and mature.

Paradoxically, while parents refuse to provide structure, they also tend to treat everything as trauma and work to protect their children from anything negative. It’s a one-two punch that fails to regulate your child while simultaneously denying them access to challenges that foster growth.

Let’s swing back to that kid in the airport. He doesn’t want ‘gentle;’ he wants structure. He wants a parent. He’s looking for an adult who holds back the chaos, allows them ample freedom to explore, and, most importantly, one who sets firm boundaries that help them mature. They don’t want a friend, a partner, or a therapist. They want a parent. They need a parent.

There’s also a tendency to pathologicalize children’s behaviors as autism, ADHD, and many more, on an ever-increasing plethora of self-diagnosis as a way to justify their lack of regulation and maturation. No, Timmy isn’t ‘sensitive.’ Timmy is being an authoritarian, desperately trying to enforce some semblance of structure because his parents can’t/won’t. Just like the dogs in Herriot’s story, five-year-old Timmy is trying to step into the role of alpha and failing because he’s five, not thirty-five.

Growing from a Gentle or Helicopter Parent into an Authoritative Parent isn’t permission to be a tyrant, but it is permission to set firm boundaries, demand respect, exert authority, and create structure for your children to thrive. As I like to say: “With my kids, I’m a benevolent dictator. They aren’t mature enough to handle the complex idiosyncrasies of life yet, and my goal is to develop them into independent individuals with an end state of having an anarchistic relationship with each of them as they become adults.” I’m authoritative.

Summary

In the book 12 Rules for Life, Rule #5 covers this topic well: “Do not let your children do anything that makes you dislike them.” That mom in the airport didn’t like her son at all on that flight. I can’t imagine the discordance in her brain as she processes her love and affection against her child’s spiteful disdain, rejection, and malice. And come to think of it, disdain is a perfect word to describe that child’s expression. Clearly, something is wrong when your gentle parenting style continuously ends with disdain.

This is why I advocate raising your children like we raise our dogs. It’s a simple, yet counterintuitive reminder that, lacking structure, order, and accountability, your children have no protection from the chaos and no ability to learn how to manage that chaos based on your example. Don’t be a tyrant, but be a parent. One that understands that you’re in charge, your kids can do hard things, and those hard things are helping them grow through the healthy structures you provide. This teaches them temperance, patience, and focus that mature their agency.

Did you enjoy this post? If so, please hit the ❤️ button above or below. This will help more people discover Substacks like this one, which is great. Also, please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid member keeps these essays open for everyone. Hurry and grab 20% off an annual subscription. That’s $24 a year or $2 a month. It’s just 50¢ an essay and makes a big difference.

Further Reading from Authors I Appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

Goatfury Writes All-around great daily essays

Never Stop Learning Insightful Life Tips and Tricks

Cyborgs Writing Highly useful insights into using AI for writing

Educating AI Integrating AI into education

Socratic State of Mind Powerful insights into the philosophy of agency

Brubaker, L., & Udell, M. A. R. (2023). Does pet parenting style predict the social and problem-solving behavior of pet dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)? Animal Cognition, 26(1), 345-356.

Obviously, we have a lot of adults raising their dogs poorly, too, but it still makes for a good juxtaposition in the argument.

Apparently, Peanut is a wonderful beagle, but she’s still a terrible lab! 🤓

Shrier adapted from Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907.

Briggs, Rahil D. PsyD. (2024, June 27). Gentle Parenting Doesn't Mean Permissive Parenting Psychology Today.

Hannah Spier, MD recently wrote on this topic on how Gentle Parenting is, ironically, leading to narcissism in the kids while they, in turn, end up accusing everyone else of narcissism. I think it’s a classic ‘looking into a mirror,’ situation. Here’s Hannah’s great essay:

Jung, C. G. (1959/1968). Psychological aspects of the mother archetype. In H. Read, M. Fordham, & G. Adler (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (2nd ed., Vol. 9, Pt. 1, pp. 75–110). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1938)

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907.

I think the term "gentle parenting" is an interesting example of the rapid semantic drift that happens when an idea is disseminated through the internet and gets warped by thousands of social media second hand explanations.

In its original formulation by Sarah Ockwell-Smith, there's nothing in Gentle Parenting that says parents should beg or bribe their children rather than saying no and maintaining a firm boundary. The gentle part is about trying to remain calm, being consistent, and avoiding harsh punishment— exactly as you would a dog.

I don't shout at my dog, hit her, or put her in isolation to teach her a lesson. But I do maintain boundaries. If she snaps at another dog, I'll remove her from the situation; if she's not able to resist the temptation of deer scent, she goes back on the lead. I don't shout or hit my four year old either, or put him on a naughty step. But I do maintain boundaries around acceptable behaviour — and try and give him the skills to manage his emotions.

Totally agree on all points but one… “demanding respect.” As the saying goes, “Respect is earned.”

But this is a natural outcome of authoritative parenting. When I look at any kids or adults today that had gentle parents (by today’s standards), they do not respect their own parents. Typically, when you think of a sport’s coach, or that grandfather, or teacher that expected more from you and didn’t pander or give into your bullshit, but saw through you, called you out, and cared enough to set you straight… they tend to create a lasting imprint and gain the respect of the child who in turn talks about that authoritative influence in their lives that they respect so much.

I do understand demanding respectful behavior as an expectation and boundary though. 🫡