Nothing Good Happens After 4PM

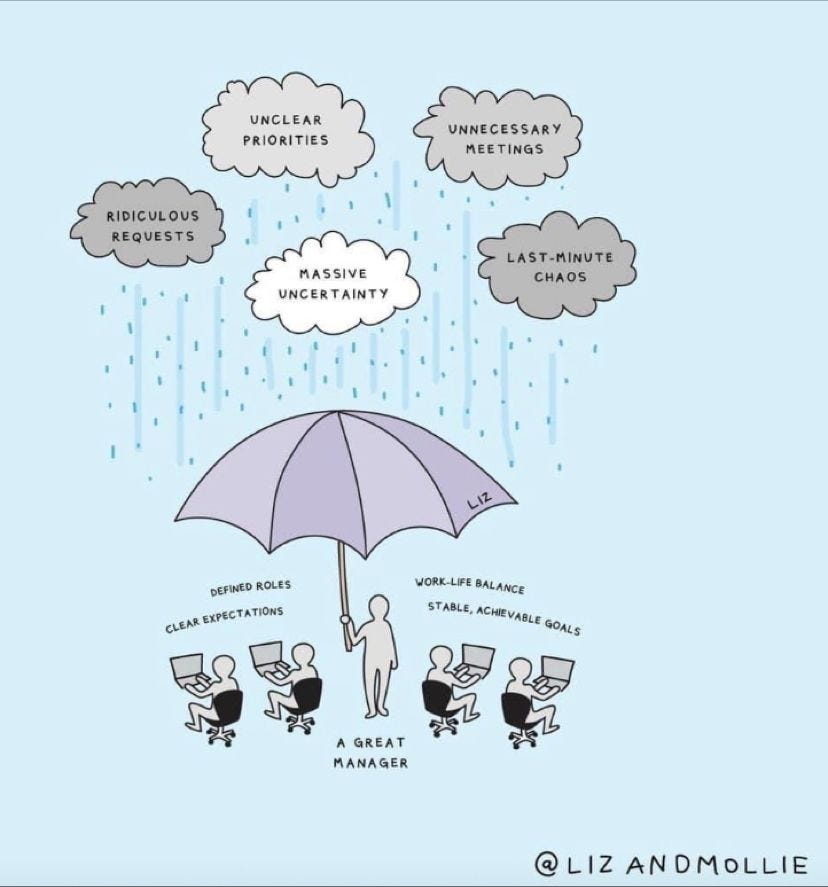

Creating a safe and consistent environment for employee success

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays take common topics and investigate them from different perspectives and disciplines to come up with unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic pokes at a problem I see all too often in businesses. It revolves around all the talk of alignment, execution, and stability and yet, when the first deviation or last-minute request appears, the leadership turns into reaction mode and throws it all out the window. This essay explores that phenomenon and weaves together some of the previously discussed counterintuitive opportunities so that anyone can provide a safe, stable, and productive work environment.

When I was a young officer in the Army my wife of just six months commented, “I don’t think your commander likes his wife!” This observation emerged because he’d regularly ask us Lieutenants to stay after closing formation to handle some planning, response, or other activity. Inevitably it wouldn’t be a 15-minute mob attack to a quick resolution but would drag on for upwards of 2 hours with little value.

I finally got so sick of if that I’d ensure my daily plan allowed me to close my platoon’s formation myself, somewhere else, and have the excuse to just drive home. The impact of that decision? I had happier soldiers and a happier wife, and I didn’t actually miss anything.

Fast forward a few years into my civilian career,

and add in a new baby and I ran into the same thing. I’d start my work at 6:30 AM and strive to be out by 3:30 to 4 PM to get home and have time to be with my daughter before her 7 PM bedtime. That way my wife and I could have some quiet time together until we went to bed.

Having learned from the Army, I was vocal about my exit time and unashamedly leveraged my infant daughter as the reason. This schedule allowed me to completely confirm my suspicions that nothing good happened after 4PM as this was the common afternoon progression:

4:04 PM: Director concludes final meetings for the day and jots off an e-mail or instant message (IM) asking for data, insight, report, or presentation about a topic that a Senior Leader asked him. He typically didn’t specify the timeframe and it sounded like it was urgent.

4:15 PM: Team on hand starts to scramble for the information. The first e-mail from the Director was unclear on the exact scope and so a quick huddle is convened.

4:45 PM: First-pass thoughts are sent back to the Director and the team waits for the response.

5:05 PM: Director responds that this wasn’t what he thought it was going to be and becomes worried that the quick response might not provide the right answer. A quick phone call occurs, and it just confuses the situation.

5:45 PM: One miscommunication after another is starting to lead to full-blown panic that we might not be aligned with the senior leadership.

6:45 PM: The team keeps churning away, but energy is ebbing and they’re frustrated.

7:09 PM: The team lead finally calls it for the night and takes in on themselves to work it the next day.

This was the life of so many of my co-workers and, sadly, was a lauded behavior for many of my unfortunate peers. I’d hear stories all the time of last-minute scrambles morphing into late night work sessions.

In the meantime, I was at home, spending time with my daughter, and avoiding the chaos. The next morning I’d get into the office at my normal time, and it would look like this:

6:30 AM: I log into my computer and find my email inbox stuffed with a flurry of e-mails capturing the activities from the evening before. I start to read through the drama and contextualize it.

6:45 AM: I realize the Senior Leader was asking a different question than the Director asked the team based on the larger systems context. I see that the team was close to the answer but was missing the ‘Why’.

7:15 AM: I’ve finished scraping the information together and compile it with some supporting datasets.

8:00 AM: After a rest and a review I’m comfortable with the answer and send it out to the Director and team.

8:15 AM: Director responds that it’s great and thanks me for the fast response and clarifies that it’s not due for another week, but he’s forwarded it to the requestor.

This was the foundational pattern, often several times a week, week after week after week. Really, nothing good happens after 4 PM. All you get is chaos.

Digging Deeper

I’ve found there’s one major driver for these behaviors at all levels of leadership. It is rooted in leaders not fully understanding the impact of these requests on others. It happens at all levels. The Vice President thinks it’s an ‘easy ask’ and the Director either doesn’t know or doesn’t push back if they do know. This continues to flow down and become more and more complicated.

For example, I was once advising a Vice President (VP) as their Six Sigma Expert. I was able to sit in on senior staff meetings as well as working down deep within the organization. After watching the VP ask questions and then being on the receiving side helping the teams respond to them, I quickly understood that few people in the chain understood how much effort went into answering these questions.

I recommended to the VP that she change the way she asked the question. Instead of saying “What’s the impact of XXX on YYY” we just appended a different question; “How long will it take, and how much will it cost me, to find out the impact of XXX on YYY”. She then gave the leaders 24 hours to find out the answer. The first time she asked a question this way, the answer floored her. It would take 2 weeks and close to $50,000 to have her ‘simple’ question answered.

What this shift of perspective allowed was to uncover what’s called the Hidden Factory; those things that occur, that are not seen or acknowledged, but drive inefficiency. Uncovering these issues in time and cost allowed the VP to ask a different question related to that inefficiency which almost always also resolved her initial question. Further, understanding why it would take 2 weeks and $50,000 to answer the question also helps indicate the larger systems implications affecting everything.

While it sounds simple to say that leaders don’t fully understand the impact, the problem is actually multi-layered and there’s certainly no easy button to press as many leaders hope for. It takes a lot of work to tease this all apart but luckily, we’ve covered many of the solutions in previous essays and so we’ll weave those together now.

The Solutions

The challenge in this situation revolves around three categories that need to be addressed: Systems, Behaviors, and Leadership. It’s tempting to merge all the layers together, but I think it’s essential to address each separately yet as three legs to the solution stool. If you ignore a leg, the stool will tip over.

Solving the systems problem means applying Systems Thinking with curiosity, the humility to accept we don’t know as much about the systems as we’d like to think, and intentional reframing to ensure a holistic perspective. It’s also essential to understand whether you are dealing with a pile of process ‘band-aids’ that are obfuscating the true issues so that you can address the full system to better understand the behaviors.

Behaviors are more complicated as you have to recognize that those dutiful reactions after 4PM are a sign of the Successfully Unsuccessful; those people who keep getting rewarded even when chaos reigns in the system. These industrious executors are the prime driver of Functional Stupidity within organizations that resist change and improvement all while talking about achieving the next level. It is essential to name and be honest about the negative behaviors in order to address the final solution category.

To address Leadership the first step is to ensure they are providing Direction, Energy, and Accountability thereby avoiding three common leadership fallacies. With this framework in place teams can then start to advocate for more Lazy Leadership. This counterintuitive concept is actually the key that I used to counter the problems described above. Lazy leadership is fundamentally knowing when the wrong question is being asked, when more effort won’t solve the problem, when to just take a tactical pause and let the situation develop, and when to bring in new resources. These two solutions, paired with the Systems and Behaviors help us actually move the needle in innovation, design, and execution of complex solutions.

We’ve addressed these topics individually in the past, and you can click through on the hyperlinks to read those essays, yet it’s fascinating to see how each of these counterintuitive concepts weave together into an even larger systems view that can be applied to create a safe, stable, and productive work environment for everyone.

Enjoyed this post? Hit the ❤️ button above or below because it helps more people discover Substacks like this one and that’s a great thing. Also please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Further Reading from Authors I really appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

Looking for other great newsletters and blogs? Try The Sample

Every morning, The Sample sends you an article from a blog or newsletter that matches up with your interests. When you get one you like, you can subscribe to the writer with one click. Sign up here.

This is the best article on the art of management I have read in a very long time. Well done, Lieutenant Woudenberg!