What Right Looks Like

Lessons in Projection vs. Actions

Welcome to Polymathic Being, a place to explore counterintuitive insights across multiple domains. These essays explore common topics from different perspectives and disciplines to uncover unique insights and solutions.

Today's topic shares some insights from my time in the Army on how to focus on the right performance indicators to ensure success. We’ll explore how many people pay attention to the superficial instead of understanding that what right really looks like is a mindset of dynamic and disciplined execution.

Intro

“Hey son, you’re looking a little out of regulation, aren’t you?”

I relaxed my face, took a breath, and turned crisply toward the owner of that snide drawl. Quickly apprising the situation and rank, I responded, “Hey, Sergeant Major, I’m not sure what you mean?”

The spark in the eye and the subtle curl of the lip told me I was in for an adventure as he gestured toward my appearance. “This,” he paused. “What’s up with this?”

I reached down and tugged my uniform straight, combed my fingers through my hair, and asked, “I’m sorry, Sergeant Major, what’s up?” I looked more closely at the man, noticing his perfectly crisp uniform, razor-sharp creases, and boots shined to a mirror finish. My eyes flicked up to his face, taking in his fresh high and tight haircut, and then settled on his eyes as they bored into mine.

“This,” he repeated, gesturing to my uniform, “and that.” He pointed to my hair. “You’re out of regs.”

“I’m sorry, Sergeant Major, I just got back from the field and was grabbing some gear for one of my Soldiers, and then heading back, and what’s wrong with my hair?”

“It’s a little long init?” he sneered.

“Sergeant Major, the AR670-1 states that the hair may be no longer than three inches on top, be tapered to the neck, and present a clean and kempt appearance.” I reached up, plucked a hair, and measured it on my Leatherman. “Two and a half inches, Sergeant Major, and it’s a little messy because it’s hot and humid out there. My uniform is clean, if a little sweaty, and my boots are in good condition and brushed and polished right before I came in.”

“You just gotta show soldiers what right looks like, Lieutenant.”

The rising blood heated my neck. “I’m sorry, Sergeant Major, let’s talk about what right looks like.” I leaned forward. “First, you haven’t addressed me as Sir, you aren’t standing at the position of attention, and you are condescending, all violations of the Army’s customs and courtesies. Second,” I ramped up. “The AR670-1 specifically states that you must not crease-press your uniforms and abide by the wash-and-wear instructions. Can you please remind me of the wash-and-wear instructions?”

The Sergeant Major’s face was turning purple while I continued, “I’ll help; it says ‘do not starch.’” I paused before concluding, “So while you say I need to show Soldiers what right looks like, I’m not in violation of anything, and you are in violation of the AR670-1 and the customs and courtesies of the Army.”

I spun on my heel and strode to the checkout to avoid what I expected would be a sizeable blast radius behind me.1

What does right look like?

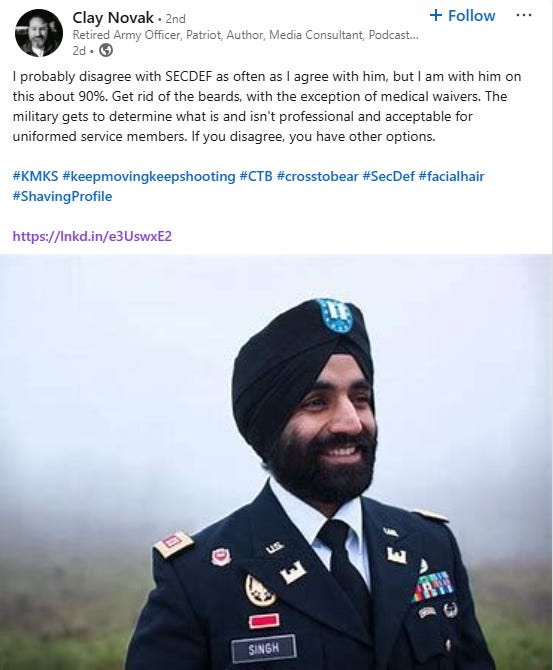

This experience wasn’t uncommon while I was in the Army, but the memory was reignited by a recent LinkedIn post pictured below. It noted that the proliferation of beards and certain religious headgear in the Army is interpreted by some as unprofessional.

The comments did not disappoint, with many calling out this Shik for his beard and headgear as unprofessional based on an arbitrary definition of what right looked like. Worse was the exceptionally thin logic many had that didn’t go much deeper than, “That’s not how I had to do it.” Their reaction centered on what they thought looked professional, rather than any real merit.

This is ironic because the Sikhs are renowned for their warrior traditions. This reputation started with Guru Gobind Singh's formal organization of the Sikhs as the Khalsa in 1699, adopting a saint-soldier model where the saint (Sant) is grounded in humility, meditation, and compassion, and the Soldier (Sipahi) is trained and obligated to defend others. The Khalsa wasn’t about conquest but moral courage and service.

They were such exceptional soldiers that the British recognized Sikh military discipline and loyalty, integrating them as a major component of the British Indian Army. They served with distinction in Afghanistan (in the earlier wars), both World Wars, North Africa, Burma, Europe, and the Middle East. Their performance earned them recognition as fearless warriors.

Honestly, I want more Sikhs in my units because I often saw officers and NCOs who projected competence in their appearance as a form of compensation for their actions. They’d show up starched and crease-pressed, mirror-shined boots, with a fresh high and tight each week, baby smooth face, and couldn't lead a team out of a wet paper bag. They’d be doing better if they'd put as much effort into their Field Craft (tactics and techniques) as they did worrying about looking good.

I saw this with a Seargant of mine who’d show up each Monday starched and pressed and fail to execute all week long. After a month of this, I told him he’d be low crawling the starch out of his uniform the next time. After two Mondays of that, he stopped focusing on the wrong things, and we started improving the rest of his performance.

It’s also more than just the annoyance of pomp and circumstance that angers me about the starched and pressed crowd; It’s the functionality. The reason the AR 670-1 states 'no starch' is that starch clogs up the fibers, making you hotter in the summer and colder in the winter. One Lieutenant in Korea bragged about his ‘super’ starch and then, in the motor pool in 90°F and 90% humidity, was wiping away handfuls of starch as it oozed out from the sweat just before he passed out from heat exhaustion. Nothing says professional more than leaving a white starch smear on the concrete after being laid down and medevac’d.

Actions vs. Looks

Conversely, the core group of lieutenants I served with in Korea took a more relaxed approach. We wore our hair as long as possible, broke curfew in Seoul as often as possible, and pushed the boundaries whenever possible, yet always executed our missions as best as possible. The result was some of the highest performing platoons and companies in the division, and we regularly won competitions handily.

When a new Battalion Commander arrived, he nearly lost his mind on our ‘hippie hair.’ Thankfully, our Command Sergeant Major pulled him aside and told him to watch the performance, not the hair. After a few months, the Commander gruffly took us aside and congratulated us on our performance, the relaxed atmosphere of the battalion, and how the focus on performance was also driving improved behaviors among the soldiers. When he stopped focusing on looks and started focusing on actions, the whole unit got better.

That is what showing soldiers what right looks like.

I have to add the required caveat that this isn’t advocating for the abolishing of all uniform standards, but the recognition that many people are focusing on the wrong measures of success, while others hide behind those measures to mask real performance issues. Because, over time, the standards have changed, but the necessary discipline of combat has remained the same. This is where it’s crucial to identify the key areas to measure performance, a topic we explored earlier in the essay, Understanding Success.

Summary

Back to that LinkedIn post and the Sikh gentleman with the beard. I don’t know how good his performance is, but I can tell you, I wouldn’t worry whether his dastar (turban) or his beard were a problem. I’d see if his actions and behaviors demonstrated competence. He’s also a man who comes from a history of proven warrior ethos, is willing to serve in our Army, with his convictions, and honor what he feels is right, even if it means standing out. He’s not capitulating to the ‘easy’ way of blending in.

It’s a similar concept that we’ve explored in how we reframe problems, reject common success measures, and ensure focus on the right objectives. It’s also the fundamental ethos behind the counterintuitive insights we uncover each week. It’s not about credentials, uniformity, language conformity, or other forms of gatekeeping. What right looks like is a mindset of dynamic and disciplined execution.

If you’re curious about more insights from my time in the Army, check out The Enemy’s Gate is Down:

Did you enjoy this post? If so, please hit the ❤️ button above or below. This will help more people discover Substacks like this one, which is great. Also, please share here or in your network to help us grow.

Polymathic Being is a reader-supported publication. Becoming a paid member keeps these essays open for everyone. Hurry and grab 20% off an annual subscription. That’s $24 a year or $2 a month. It’s just 50¢ an essay and makes a big difference.

Further Reading from Authors I Appreciate

I highly recommend the following Substacks for their great content and complementary explorations of topics that Polymathic Being shares.

Goatfury Writes All-around great daily essays

Never Stop Learning Insightful Life Tips and Tricks

Cyborgs Writing Highly useful insights into using AI for writing

Educating AI Integrating AI into education

Socratic State of Mind Powerful insights into the philosophy of agency

Fun note, it happened to be the Deputy Division Commander’s Sergeant Major, and I had to go see the General the next week. When I shared my side, he said, “Son, you’re right, but pick your battles better next time.”

Love this. In the spirit of polymathic being gathering excellence from multiple domains, your piece makes me think of this Alan Watts riff of eastern philosophy of confusing symbols for the object itself.

Put to nice music from an album’s interlude:

https://on.soundcloud.com/viVuaBbMYzHPteKPny

(Also I found your great essay from Sam Alaimo’s repost)

Looks like a well known NYT columnist is glomming onto the "Poly" thing.

----

Welcome to Our New Era.

What Do We Call It?

By Thomas L. Friedman

For the past few years, I have had to ask myself a question I never asked before in my life: What should we call the era we’re living in today?

I was born into the “Cold War” era, and most of my career as a columnist was in the “Post-Cold War.” The latter era — those decades since 1989 characterized by American unipolar dominance — ended in the 2020s with the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, followed by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which exploded Europe’s Cold War and post-Cold War security architecture, followed by China’s emergence as a true peer economic and military rival to the U.S.

My initial thought was that we should call this new epoch the “Post-Post-Cold War,” but that made no sense. No, we have arrived at a moment that is much more than the aftermath of a largely bipolar superpower rivalry born in the mid- to late-1940s. It’s the birth of something novel and highly complex to which we all must adapt, and quickly — but what to call it?

Many climate scientists call our current epoch the “Anthropocene” — the first human-driven climate era. Many technologists call it the “Information Age” or now the “Artificial Intelligence Age.” Some strategists prefer to call it “the Return of Geopolitics” or, as the historian Robert Kagan put it, “the Jungle Grows Back.”

But none of these labels capture the full fusion taking place between accelerating climate change and rapid transformations in technology, biology, cognition, connectivity, material science, geopolitics and geoeconomics. They have set off an explosion of all sorts of things combining with all sorts of other things — so much so that everywhere you turn these days binary systems seem be giving way to poly ones. Artificial intelligence is hurtling toward “polymathic artificial general intelligence,” climate change is cascading into “poly-crisis,” geopolitics is evolving into “polycentric” and “polyamorous” alignments, once-binary trade is dispersing into “poly-economic” supply webs, and our societies are diversifying into ever more “polymorphic” mosaics.

As a foreign affairs columnist, I now have to track the impact and interactions of not only superpowers, but also super-intelligent machines, super-empowered individuals taking advantage of technology to extend their reach and super-global corporations, as well as super-storms and super-failing states, like Libya and Sudan.

I was musing about all this one day with Craig Mundie, the former head of research and strategy at Microsoft. I told him that in nearly every domain I was writing about lately, the old binary left-right systems were giving way to multiple interconnected ones, and, in the process, shattering the coherence of both the Cold War and post-Cold War paradigms.

At one point Mundie said to me, “I know what you should call this new era: the Polycene.”

It was a neologism — a word he just made up on the spot and not in the dictionary. Admittedly wonky, it is derived from the Greek “poly,” meaning “many.” But it immediately struck me as the right name for this new epoch, where — thanks to smartphones, computers and ubiquitous connectivity — every person and every machine increasingly has a voice to be heard and a lever to impact one another, and the planet, at a previously unimaginable speed and scale.

So, welcome to the Polycene. It’s been an interesting ride getting here.

...

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/10/opinion/era-technology-poly-epoch.html